The journey through life introduces a myriad of biological changes, particularly as one reaches advanced age. Among the most significant transformations involves the relationship between aging and cancer risk. Interestingly, this relationship exhibits a dual character: while the risk of developing cancer generally increases as individuals transition into their 60s and 70s, studies reveal a perplexing decline in cancer risk after reaching 80. Understanding this phenomenon necessitates an examination of the underlying biological mechanisms that govern these opposing trends.

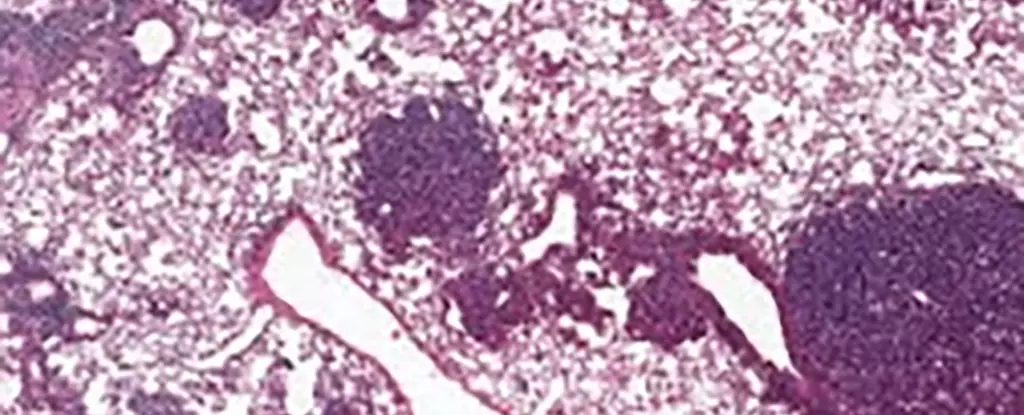

Recent research has shed light on lung cancer through experiments conducted on mice, focusing on a type of stem cell known as the alveolar type 2 (AT2) cell. These specific cells contribute significantly to lung tissue regeneration and frequently serve as the origin for various lung cancers. Observational data revealed that older mice exhibited increased levels of a protein termed NUPR1, which appears to modify the functioning of AT2 cells dramatically. Notably, while aging cells accumulate iron, their behavior suggests an iron deficiency, creating an environment where cell regeneration falters, thus hampering both healthy cellular growth and the proliferation of cancerous cells.

This paradox of seeming iron deficiency amidst actual accumulation emphasizes an essential aspect of aging biology. Xueqian Zhuang, a cancer biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, highlighted the diminished capacity of aging cells to renew themselves, which inherently limits their potential for unchecked growth, a defining characteristic of cancer cells. This observation marks a significant turning point in our understanding of cancer dynamics across different ages.

What stands out in the findings from this study is not merely its relevance to mouse models but the broader implications for human health, particularly regarding cancer risk. Similar processes were uncovered in human cells where increased levels of NUPR1 corresponded to restricted iron availability. The potential of manipulating iron metabolism as a therapeutic avenue for older adults offers a promising perspective for researchers. Not only could enhancing iron levels rejuvenate cellular regeneration, but it may also have therapeutic value in mitigating long-term effects from conditions such as COVID-19, thereby restoring lung function.

The interplay between iron and a specific type of cell death known as ferroptosis further complicates this discussion. Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death induced by iron levels, and it appeared that older cells demonstrate resistance to this mechanism. This resistance holds critical implications for developing cancer therapies that leverage ferroptosis as a treatment strategy. The timeliness of administration with respect to a patient’s age may become a crucial consideration.

Tuomas Tammela, another cancer researcher from the same institution, underscored the salient point regarding youth behaviors and cancer risk. His findings suggest that the biological events occurring in younger individuals put them at a higher risk for cancer—further emphasizing the urgency of preventive health measures. Actions such as discouraging smoking and sun exposure emerge as critical strategies in reducing future cancer incidence. Tammela’s insights significantly shape public health approaches and underscore the importance of collective efforts to foster healthier behaviors in younger generations.

Despite these promising revelations, much remains uncertain about the aging process’s impact on cancer biology. A more nuanced understanding of the connection between age, cancer risk, and treatment efficacy is crucial. As we aim for a future of personalized cancer treatments, the individual’s type and stage of cancer, as well as their overall health status, must take center stage. Continued research into NUPR1’s role and its relationship with stem cell functions in both healthy and cancerous tissues is vital in shaping effective, tailored therapeutic strategies.

While it is evident that advances are being made in cancer research, further exploration is necessary to grasp how the aging process fundamentally alters cancer dynamics. Only then can we devise interventions that truly address the complexities inherent in the aging population and their risk for cancer.

Leave a Reply