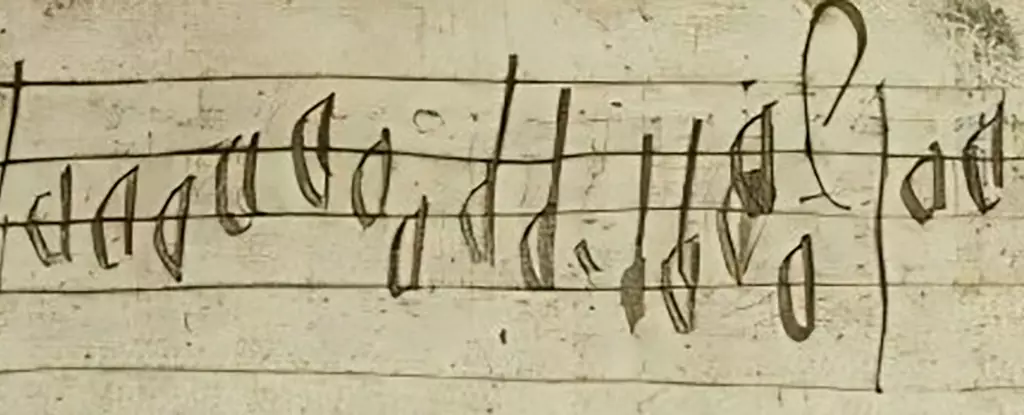

Music is not merely an art form; it serves as a temporal bridge to our past, connecting us to the cultural fabric of different eras. A team from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh recently unearthed a musical fragment dating back to the 16th century, found in the margins of the Aberdeen Breviary—a seminal religious text that marked a pivotal moment in Scotland’s literary and spiritual history. This 55-note snippet provides a rare glimpse into sacred music practices that have largely been lost to history. The interplay between literature and music emphasizes the interdisciplinary potential inherent in historical research, allowing us to appreciate the cultural tapestry of a time long gone.

The Aberdeen Breviary holds tremendous historical weight as the first full-length book printed in Scotland. While its primary function was to offer prayers and liturgical guidelines, it harbors more than religious significance. The accidental discovery of musical notation within its margins transforms our understanding of this important artifact. The implications of finding music inscribed in such an influential text speak to the intersection of the sacred and secular in pre-Reformation Scotland. The finding expands existing narratives of Scottish culture and reveals that music was an integral part of religious life, contrary to the conventional view that suggests a barren musical landscape before the Reformation.

Researchers were able to connect the discovered music to the Anglican chant known as “Cultor Dei, memento,” also referred to as “Servant of God, remember.” Although the fragment remains ambiguous in its intended application—whether for instrumental or vocal performance—the very existence of this notation indicates a complex musical landscape that accompanied the liturgy of the time. Musicologist David Coney articulates the transformative nature of this discovery, noting how a scrap of music can evoke a hymn that lay dormant for nearly five centuries. This underlines a broader theme in musicology: the importance of fragmentary evidence in reconstructing cultural practices.

The composition is identified as polyphonic, allowing for multiple melodies to coexist, a feature that exemplifies the rich musical environment assumed to exist during this period. However, the absence of formal titles or attributions poses questions about the educational practices surrounding music—were these traditions passed down verbally, or were they part of a formal system of musical instruction, and how widespread were they in Scotland?

Challenging Established Notions of Pre-Reformation Music

Historically, scholars have often relegated pre-Reformation Scotland to a category devoid of significant musical output. Musicologist James Cook challenges this narrative by pointing out that the recent findings emphasize a rich tapestry of sacred music that existed prior to the Reformation upheaval. Instead of viewing Scotland as a musical wasteland, this discovery illustrates that, like Europe-wide traditions, Scotland thrived with high-quality music. This newly revealed landscape opens avenues for further research, encouraging scholars to reconsider the extent of musical activity during this crucial transitional period.

The researchers’ inquiry did not conclude with this singular fragment. They examined the provenance of the Aberdeen Breviary and traced connections to significant locations such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel, revealing the cultural networks that may have existed. This ambitious project has catalyzed an eagerness to investigate other historical texts, with scholars hopeful that similar musical notations may be lurking in the margins of other 16th-century books. Such future explorations could further enrich our understanding of Scotland’s musical heritage, guiding researchers to unexpected insights and potentially reshaping our perception of historical musical practices.

The remarkable rediscovery of this musical fragment serves as a potent reminder of the profound impact that historical research can have on our understanding of cultural practices. Each note uncovered allows us to reconstruct not just the sound of a bygone era but also the rich traditions and beliefs that shaped musical expression in Scotland. The intersection of music, religion, and history posits new dimensions for exploration, where every blank page and forgotten tune holds the potential for a story waiting to be told. As we look back, we are also challenged to consider how future generations might perceive today’s musical landscapes, prompting us to protect and preserve our own cultural legacies.

Leave a Reply