Recent research has reignited the debate surrounding the potential cognitive effects of antibiotic use among older adults. Conducted over approximately 4.7 years, the study managed to draw crucial conclusions about the relationship between antibiotic prescriptions and dementia risk in a defined group of healthy older adults. Led by Andrew Chan and his team from Harvard Medical School, the study examined data gathered from a substantial cohort of 13,571 participants aged 70 and above, enrolled in the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial. The findings, published in the esteemed journal Neurology, indicated that there was no significant correlation between antibiotic use and the incidence of dementia in the participants, with relevant hazard ratios affirming a lack of association.

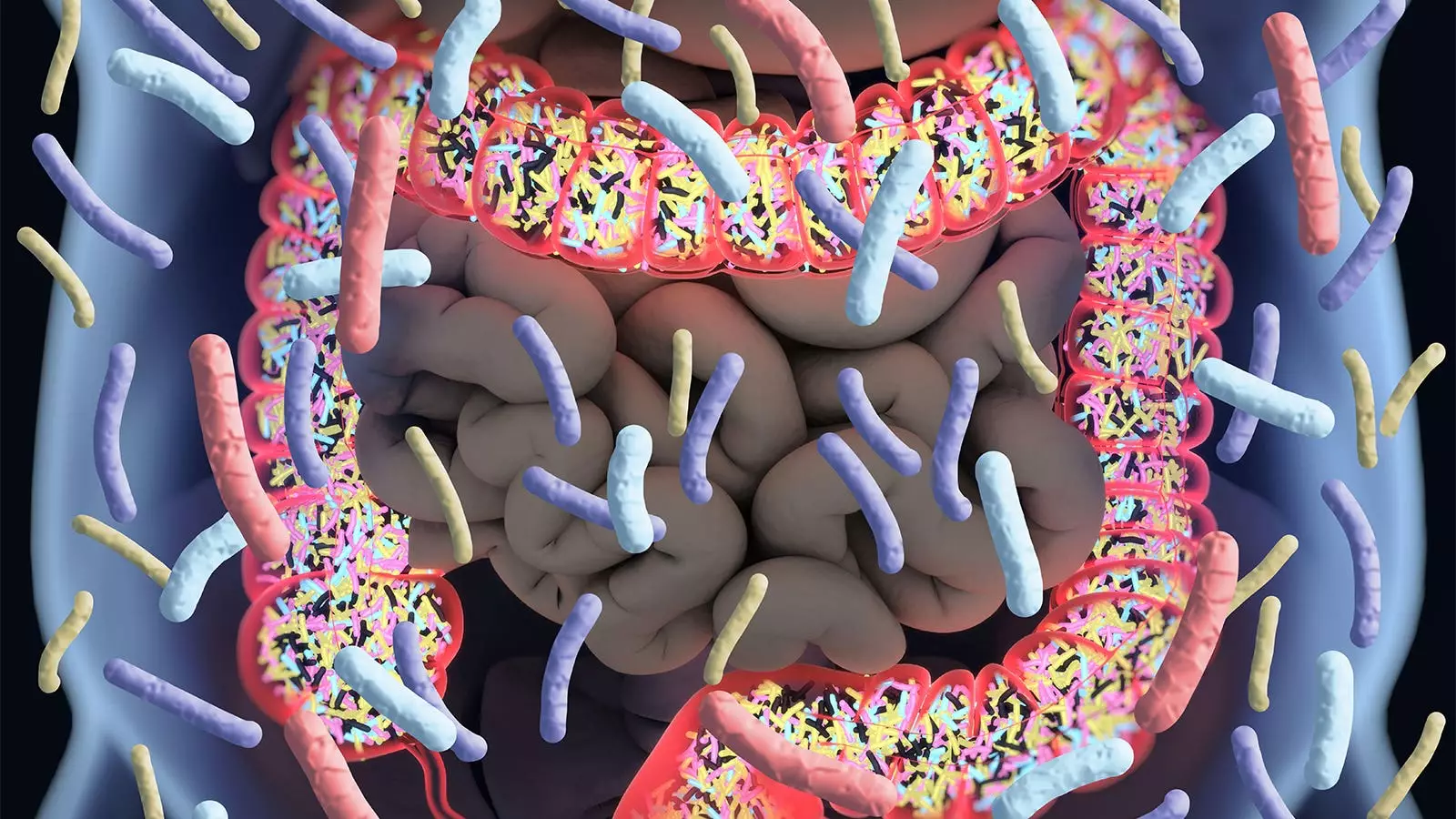

One of the standout conclusions from this investigation is that despite the widespread concern regarding antibiotics disrupting the gut microbiome—which is believed to play a role in various aspects of health, including cognitive functioning—no adverse long-term cognitive effects were observed. This notion may alleviate fears surrounding antibiotic prescriptions in older adults, who are more likely to face microbial imbalances due to aging or illness.

However, the implications of this study are anything but straightforward. While the results may suggest that antibiotics do not necessarily pose a direct threat to cognitive health in healthy older adults, it’s essential to recognize the limitations of the research. As articulated in an editorial by Wenjie Cai and Alden Gross from Johns Hopkins University, caution is required when extrapolating these findings to all older individuals. The trial’s participants were relatively healthy upon entry; hence, drawing conclusions applicable to a broader demographic, particularly those with pre-existing conditions that might complicate health dynamics, may be misleading.

Additionally, the baseline health status of the study cohort—free from serious disabilities or major illnesses—means that the relationship between antibiotic use and cognitive decline could differ significantly in populations characterized by comorbidities or more significant health challenges. This discrepancy highlights the necessity for further studies that explore how other health variables and antibiotic exposures may correlate with cognitive decline in various elder populations.

Adding complexity to the narrative, existing literature on the relationship between antibiotic use and cognitive health presents a mixed bag of findings. Previous studies have produced varied results, showcasing inconsistencies in how different populations respond to antibiotics. For instance, during the Nurses’ Health Study II, participants encountered a more alarming scenario where prolonged antibiotic exposure in midlife was linked with diminished cognitive performance years later.

Contrastingly, a randomized trial revealed that daily oral antibiotic treatment led to a temporary attenuation of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients. However, subsequent analyses painted a different picture, failing to replicate the earlier promising results. Such discrepancies demonstrate a crucial need for a deeper scientific inquiry into how antibiotic exposure may intermittently influence cognition, suggesting that the implications may not be uniform across demographics or health statuses.

The methodology employed in Chan’s study is commendable; however, it also introduces areas of possible concern. The reliance on filled prescriptions to infer actual antibiotic use—rather than direct reporting from participants—can raise questions about the accuracy of the data. Did all participants take the antibiotics they were prescribed? Were there variations in adherence or other confounding factors that were not accounted for in the analysis?

The study also highlighted a critical remark about the classifications of the antibiotics themselves, indicating that even drug classes such as fluoroquinolones, which can cross the blood-brain barrier, showed no particular association with cognitive deterioration. The implication here adds to the complexity: while certain antibiotics may have more pronounced effects under specific conditions, the broader relationship with dementia remains elusive in this cohort.

While the study led by Andrew Chan and colleagues provides essential insights and perhaps a sense of reassurance regarding antibiotic use and dementia risk in an otherwise healthy older demographic, it simultaneously underscores the intricacies of this relationship. Future research should delve deeper into heterogeneous population subsets and consider a wider array of factors influencing both microbiome health and cognitive functions among the elderly. As our understanding of the microbiome and neuroscience evolves, it is critical that we approach the topics of medication, cognition, and aging with nuanced caution and robust scientific inquiry. This duality of reassurance and concern should guide ongoing exploration in the intersections of medicine, cognition, and geriatric health.

Leave a Reply